I've run across a guy, Johnny Wahl, who's farther along than I am self-publishing his own game, called Conquer the Kings. It's a chess variant that supports up to four players on a new board, with piece placement up to the players. Looks like an interesting game, although I'm not enough of a chess player to know how it would go.

More interesting to me is the production and marketing. He's gone pretty high-end with the board and box, printed in the U.S., and he's ordered standard chess pieces from China. The artwork is neat. He's got pictures of the production run, which is really interesting. It looks like (from one of his picture captions) his initial print run was 500 games, and I bet they cost him a lot with those numbers and parts - probably at least $15 a copy, maybe more, which would make the game very difficult to sell through distributors at his $34.95 retail price. But chess is a huge market, and he might find enough folks to buy up those 500 directly without having to go through distribution.

The website and publishing project comes across very much as a labor of love, which is neat. He's living the dream, as I hope to do, although I'd like to do so in a way that has at least a chance of financial success. Wahl has also got an interesting post up on his testimonials page - basically a kindly-worded rejection letter from John McCallion, boardgames editor for Games magazine. That piqued my interest, because Matt Worden (of MWGames.com) recently got a mention from John for his game Jump Gate, sold through TheGameCrafter.com, but with far better artwork and game design than other games available at TGC.

I wonder if I can get my games reviewed in Games? Sounds like great publicity, and it sounds from both of these tidbits that Mr. McCallion actually does take the time to look at the things he gets sent, even if they're not in professional packaging or available in retail stores. Intriguing.

Showing posts with label Publishing. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Publishing. Show all posts

Friday, July 16, 2010

Saturday, July 10, 2010

Xinghui

James at MinionGames.com reports a bad experience with Xinghui games here and here. They were the very low China #1 price on my earlier summary of game production quotes, and from other reports they've been quite low on nearly all bids, but the products are reported to be shoddy and low quality, so it looks like in this case you may get what you (don't) pay for.

Thursday, July 8, 2010

CloudBerryGames

I've learned of a new site, CloudBerryGames.com, that looks like an effort to bring together designers, artists, and others to help games get designed, completed, tested, and produced. They make their money by charging a small subscription fee to designers. They say they'll actually publish some of the games submitted on the site, which would be cool - I bet the economics don't work for that until/unless they grow really big, but it's an interesting idea. I haven't looked too deeply into it, but I'll look more later.

They just put up a blog post that markets them as a way to prevent idea theft - interesting, since most serious designers have moved past that particular fear so common in newbies.

They just put up a blog post that markets them as a way to prevent idea theft - interesting, since most serious designers have moved past that particular fear so common in newbies.

Labels:

Design,

Publishing

Sunday, June 27, 2010

Profile of a start-up company

Dominic Crapuchettes has an autobiographical post about his game company up at BGG (link here, via BoardGameNews.com). Interesting stuff - he's made the big time (carried by Target) and has $1.5 million in revenue, but still isn't breaking even. Some different choices than I'd have made (e.g. running up all the debt on credit cards), but I might not have lasted as he has.

A very interesting read.

A very interesting read.

Saturday, June 26, 2010

Inevitable Kickstarter project complete

The Inevitable guys have finished their fund-raising drive at Kickstarter.com, raising a total of $9,435. About $2,650 of that was from people who pledged more than you needed to pledge to get a copy of the game (including four at the $500 level). I posted previously on their efforts here.

They'd promised a print run of 100 for $3000 raised, so I imagine they're well past the costs they'll incur for 100 games. Something like 87 of their 100 games are spoken for at the site, going to pledgers, but they'll likely be able to produce an additional couple hundred games with the funds they've raised (if that's what they decide to do with the extra money).

An unabashed success, leading to a game with a big following and positive cash flow before it is even printed. Sounds like a great outcome - my congratulations to them.

They'd promised a print run of 100 for $3000 raised, so I imagine they're well past the costs they'll incur for 100 games. Something like 87 of their 100 games are spoken for at the site, going to pledgers, but they'll likely be able to produce an additional couple hundred games with the funds they've raised (if that's what they decide to do with the extra money).

An unabashed success, leading to a game with a big following and positive cash flow before it is even printed. Sounds like a great outcome - my congratulations to them.

Friday, June 25, 2010

Game production costs summary

The graph at left (click it to make it bigger) shows some results from quotes I've gotten for my card game, Diggity. I thought it might be useful to other game designers and people contemplating publishing their own games to see what I've learned.

Tuck and Setup refer to box types - tuck boxes are one-piece boxes with a flap that tucks in, like a regular playing card box, while setup boxes are usually two pieces (base and lid) with an internal platform for holding the contents in place.

These numbers are tricky to compile and to compare - even though I send the same specifications to each printing company, I don't always get the same results back. For example, some of the quotes include different kinds of boxes, or different box materials, or different card sizes, or different paper stocks and paper coating. Some of them include shipping; others do not, and I have to estimate it, which I've done here. I have only included printing and shipping charges and setup costs where appropriate; no other charges like import duties, file preparation, shipping of samples, etc.

Tuck and Setup refer to box types - tuck boxes are one-piece boxes with a flap that tucks in, like a regular playing card box, while setup boxes are usually two pieces (base and lid) with an internal platform for holding the contents in place.

These numbers are tricky to compile and to compare - even though I send the same specifications to each printing company, I don't always get the same results back. For example, some of the quotes include different kinds of boxes, or different box materials, or different card sizes, or different paper stocks and paper coating. Some of them include shipping; others do not, and I have to estimate it, which I've done here. I have only included printing and shipping charges and setup costs where appropriate; no other charges like import duties, file preparation, shipping of samples, etc.

I often got multiple quotes for different quantities from the same company; these are connected by lines. I sometimes got quotes for different products from the same company, e.g. tuck box vs. setup box (a two-piece box with a bottom and a lid). In this case, I've grouped them with a number; e.g. everything marked "China #1" comes from the same Chinese printer, while "China #2" would be a different Chinese printer.

I'm still pursuing bids, and I will not necessarily go with the lowest bidder here. There are a host of other concerns, such as product quality, the component materials, the box type, my estimates of other costs incurred when dealing with the company involved (which are higher overseas), the professionalism I perceive with the company, and others. I'd love to have a "Made in America" on the label, too, if I can afford it.

Thursday, June 24, 2010

Alien Frontiers - another Kickstarter success

Back at the end of April, I posted on another Kickstarter donation campaign, this one for a game called Alien Frontiers. Well, they're over $11,000 with just under a couple weeks to go, marking yet another successful use of Kickstarter for pre-sales. About $7500 of their pledges are at their basic, $50 level, which gets you a copy of the game. They report here at BGG that their print costs are going to be probably in the neighborhood of $15,000 (my guess is that after shipping and other costs this bleeds up toward $20,000) for 1,000 copies, so a $50 sale price per game with $15-20 production costs is probably a good target for them, although a bit steep for the retail market. I haven't seen much on the game yet, but it does seem to have a ton of bits.

I'd be interested if they manage to sell out the 800+ copies that aren't yet spoken for. I'd also be interested what ratio of their funding comes from anonymous donors. I asked a couple folks about this for earlier Kickstarter projects (see here and here), and it seems to be actually about a third to a half of the buyers in these things are unknown to the organizers - a far higher ratio than I'd have guessed.

It looks like Kickstarter is a great way to leverage game production. My earlier misgivings seem nearly entirely unwarranted in the light of these three projects.

I'd be interested if they manage to sell out the 800+ copies that aren't yet spoken for. I'd also be interested what ratio of their funding comes from anonymous donors. I asked a couple folks about this for earlier Kickstarter projects (see here and here), and it seems to be actually about a third to a half of the buyers in these things are unknown to the organizers - a far higher ratio than I'd have guessed.

It looks like Kickstarter is a great way to leverage game production. My earlier misgivings seem nearly entirely unwarranted in the light of these three projects.

Monday, June 21, 2010

Valley Games reveals some of their inner workings

Torben Sherwood is part of the new game company Valley Games, which is publishing a number of new titles, some English-language versions of German games, and some classics (e.g. Titan, which I first played in 1987). He's got a couple of posts (here and here) up at LivingDice.com.

These are interesting, but there's not a lot to go on here; there are few details, and a lot of skimming over the challenges they faced. The second article is more focused on what game designers do wrong when presenting their games to a publisher, and (more relevant to me here) some of the procedures and challenges they go through during production.

It sounds like they've had some good response at various conventions (e.g. Essen, BGG Con, GAMA) - that may be something I'll have to invest in once I get up and running, but I'm nowhere near the size they are now (17 published titles listed on their site).

These are interesting, but there's not a lot to go on here; there are few details, and a lot of skimming over the challenges they faced. The second article is more focused on what game designers do wrong when presenting their games to a publisher, and (more relevant to me here) some of the procedures and challenges they go through during production.

It sounds like they've had some good response at various conventions (e.g. Essen, BGG Con, GAMA) - that may be something I'll have to invest in once I get up and running, but I'm nowhere near the size they are now (17 published titles listed on their site).

Saturday, June 19, 2010

Production costs and financial returns

Seo at BGDF has a good very brief run-down of the economics of publishing. He's left out shipping and marketing costs, which can easily eat up the meager 1/8 of the final sales price that the publisher eventually sees, not to mention the difficulties of getting distribution, the very real risk of not selling out your print run, which leaves you deep into negative territory, and paying yourself something for the effort and investment you're putting in.

How the later commenter sees this as a very good opportunity for self-publishers is beyond me...

How the later commenter sees this as a very good opportunity for self-publishers is beyond me...

Thursday, June 17, 2010

More manufacturer options

David MacKenzie of Clever Mojo Games (the ones doing Alien Frontiers on Kickstarter.com) recommends Panda Games Manufacturing (an American company which works with Chinese manufacturers) and Xinghui (a Chinese company) in this BGDF post. There, is that enough links? :-)

I've gotten a quote from Xinghui which was very reasonable for my project - probably the best overall pricing, although it didn't include shipping, prep, and other expenses which (thanks to Dan Tibbles' excellent talk) I now know to expect from China. However, Tasty Minstrel Games had some production issues which Michael Mindes describes at his blog (and which are confirmed by seo/Seth at BGDF). Not to say Xinghui should be judged by this one experience, but it's a data point, at least.

Nine links - I think that's a record, especially for a two paragraph post. Har.

I've gotten a quote from Xinghui which was very reasonable for my project - probably the best overall pricing, although it didn't include shipping, prep, and other expenses which (thanks to Dan Tibbles' excellent talk) I now know to expect from China. However, Tasty Minstrel Games had some production issues which Michael Mindes describes at his blog (and which are confirmed by seo/Seth at BGDF). Not to say Xinghui should be judged by this one experience, but it's a data point, at least.

Nine links - I think that's a record, especially for a two paragraph post. Har.

Sunday, June 13, 2010

TheGameCrafter moving to newer, better facilities

Print-on-demand publisher TheGameCrafter.com has announced (see here) that they're moving from Wisconsin to New York, where they hope to add items they don't currently provide, like tuck boxes, game boxes, thicker game boards, and other unspecified cool stuff.

That sounds great; with the move, it also sounds like a sale of the company, although they have not announced that and I have nothing to base that on. But it seems like it would be very hard on the owners and employees to pick up and move, and they'd have no real reason to move to some place where labor and real estate are potentially more expensive just to expand their range. I've been really happy with their management, customer service, and employees - I'd hate to see any of that change with the relocation.

But if they can add more custom items (like the boxes and better boards, but also maybe some printed chits and/or tokens), that would really provide a terrific way to produce print-on-demand games that aren't limited by their current range of customizable products (only cards, boards, and stickers for disk tokens). A real printed game box (rather than the current featureless white corrugated carton) would be the biggest step towards making this a real option for marketing professional-seeming games. I hope that happens soon.

That sounds great; with the move, it also sounds like a sale of the company, although they have not announced that and I have nothing to base that on. But it seems like it would be very hard on the owners and employees to pick up and move, and they'd have no real reason to move to some place where labor and real estate are potentially more expensive just to expand their range. I've been really happy with their management, customer service, and employees - I'd hate to see any of that change with the relocation.

But if they can add more custom items (like the boxes and better boards, but also maybe some printed chits and/or tokens), that would really provide a terrific way to produce print-on-demand games that aren't limited by their current range of customizable products (only cards, boards, and stickers for disk tokens). A real printed game box (rather than the current featureless white corrugated carton) would be the biggest step towards making this a real option for marketing professional-seeming games. I hope that happens soon.

Labels:

POD,

Publishing

Monday, June 7, 2010

Summing up the GTS 09 talks

So, what are the main points I've learned listening to these couple of talks? There's a ton of good stuff in these, but I think I can distill it down to a few major points that will be most useful to me.

- You can save a goodly amount of money printing in China vs. domestically (they say between 30% and 70%), but it's a big hassle. I'm not sure it will be worth it for me if it's at the 30% end.

- The savings in China will be bigger for bigger print runs, for bigger games (i.e. larger boxes, more pieces), and for games with plastic parts. None of these potential savings likely apply to me.

- Don't start with a print run bigger than about 3,000 - that seems to be the sweet spot they recommend between getting a low enough cost-per-game balanced with any hope of ever selling them all. 5,000 is too ambitious, and 10,000 is insane.

- Design is very easy; refining a design into publishable form takes some serious effort, and printing is harder still, but none of these hold a candle to the challenge of actually marketing and selling your game.

The talks didn't give a lot of help with that last part - the marketing and selling - other than to establish a relationship with distributors and go to the trade shows.

Sunday, June 6, 2010

Estimating the reduction in cost-per-game in production runs

Listening to the GTS lectures over the past couple of days, I've learned that part of the reason prices drop so precipitously with increased numbers of games printed is that the presses churn out a bunch of games before the colors and print quality are set correctly. The number referenced by Dan Tibbles in the lectures is 1,000 games printed and discarded before they can start the actual print run. That seems like a fantastically high number, but I know very little about commercial printing, so I'll certainly accept it until I learn otherwise.

I thought I'd compare the production prices for one of my printing bids to this model, where 1,000 games are wasted. What that means is if you're ordering 1,000 games, you're actually paying for 2,000, so your cost of production should be double what it actually is per game. If you order 2,000 games, you're paying for 3,000 copies, so your costs are 150% of the actual cost. The more you order, the more your cost drops, because the wasted games become less and less of the total produced, and their costs are pro-rated over the whole print run.

Sounds reasonable, right? Well, I thought I'd test it out to see what's going on. Here's an actual bid on my game from Imagigrafx. If you're interested, I discussed this in more detail in an earlier post here.

You can clearly see the drop in cost per game with increasing production runs.

I thought I'd try to model this statistically. The bid above tapers off to something near $2 per game. So, here's a hypothetical print run, for a game that costs $2 per game to print, but with 1,000 wasted games that also cost $2 per game. So, if you print 1000 and waste 1000, it will end up costing you 2,000 * $2 = $4,000. But, you only get 1,000 games, so that comes out to an apparent cost per game of $4.

I thought I'd compare the production prices for one of my printing bids to this model, where 1,000 games are wasted. What that means is if you're ordering 1,000 games, you're actually paying for 2,000, so your cost of production should be double what it actually is per game. If you order 2,000 games, you're paying for 3,000 copies, so your costs are 150% of the actual cost. The more you order, the more your cost drops, because the wasted games become less and less of the total produced, and their costs are pro-rated over the whole print run.

Sounds reasonable, right? Well, I thought I'd test it out to see what's going on. Here's an actual bid on my game from Imagigrafx. If you're interested, I discussed this in more detail in an earlier post here.

You can clearly see the drop in cost per game with increasing production runs.

I thought I'd try to model this statistically. The bid above tapers off to something near $2 per game. So, here's a hypothetical print run, for a game that costs $2 per game to print, but with 1,000 wasted games that also cost $2 per game. So, if you print 1000 and waste 1000, it will end up costing you 2,000 * $2 = $4,000. But, you only get 1,000 games, so that comes out to an apparent cost per game of $4.

This graph has the same shape as the real offer above, which makes sense. However, the values don't line up quite right - the drop off is steeper here, and you approach the $2 more quickly than in my real data.

So, this model doesn't quite work. I tried it out with 2,000 wasted games, and it was much closer (green line below):

So, is that's what's happening? 2,000 wasted games? Probably not, in reality. I'd guess there are a bunch of actual sunk costs to setting up a print run, and those are going to have to be paid regardless of the size of the run. So rather than wasting 2,000 games, it might be much fewer, and instead, the sunk costs (one-time setup costs) are making up the rest of the elevated apparent cost per game.

But as far as the statistics go, 2,000 wasted games seems to model the real bid I was getting pretty well, even if it's not exactly what's happening. Maybe this is a good rule of thumb in estimating the drop-off in printing costs for extended print runs? Seems like an easy enough model to use.

Saturday, June 5, 2010

More GTS09 talk notes - Self Publishing

Here are my notes from listening to another talk from GTS 2009 - this one called Publishing Your Game Yourself (mp3 link here)

The speakers are from Bucephalus Games:

- Anthony Gallela

- Dan Tibbles

Here are my notes:

Opening comments

The speakers are from Bucephalus Games:

- Anthony Gallela

- Dan Tibbles

Here are my notes:

Opening comments

- Very difficult to sell your own game

- Design, production, manufacturing are easy

- Selling is far harder than all of these

- Important to figure out who target audience is - there's a risk that the game is unsellable

- 75% of new games are essentially unsellable, or they don't sell through their print run

- What's the key to your game?

- Theme? If so, then the game must pursue the theme at the expense of all other parts

- Mechanics? If so, then nothing else can get in the way

- Listen to testers - be willing to change the game - don't be too invested

- 1st 3,000 copies are sold based on appearance and artwork - NOT on theme or gameplay

- Shelf appeal is therefore key

- The box should reveal what the game is like - no surprises, no hidden stuff

- Refining a game is key - it often involves removal of features and rules, boiling it down to the central, pure elements

- Blind playtesting - very important; creates a much better rulebook

- Should you be in the room?

- Anthony says yes; your observations will let you see what assumptions they made when there were rules gaps or problems

- Some say no; reasons cited are that the players won't be honest

- Consult retailers and distributors - they are your initial direct customers

- GAMA has free focus groups at the conferences

- Talking to others is key

- Very unlikely to happen

- Game design is easy; everybody has one, so they're cheap and readily available - it's the marketing and selling that's harder and much more expensive

- Game companies don't want to work with you

- They'll often prefer to work with in-house designs, or they're small, and are actually publishing the owner/operator's design

- The numbers for this happening are a fraction of a percent chance - a few games are printed out of thousands of submissions

- To do this, you'll need to do all the development ahead of time - the testing, the rules, the layout, the winnowing out of rules

- Might be worth doing, but expect rejection

- If you're going to do it, look hard for submission guidelines, and then follow them

- Show them a good prototype - they can imagine it better, but you need to make it look good, and make it look how you want it to

- Royalties - no advance, probably 3-10%, average of 5%

- Make sure you retain rights, and you get the rights back after 18-24 months out of print

- 3,000 to 5,000 copies is a good run in the hobby market

- Don't publish with money you can't lose all of

- Don't start with a big print run - go with 3,000 max

- You'll always find flaws

- You're probably blowing your money

- Maybe 30% of games can sell 3000 copies

- Maybe 2% of games can sell 5000 copies

- Nearly nobody sells more than that on a first game

- There are 1,000 new games published every year - most of them don't get much distribution, don't get sold

- Companies are usually willing to share their sources for production in Asia

- Designers are often blind to flaws - missing words, missing typos, etc.

Distribution

- Game stores nearly always buy from distributors - there are only a few of these

- Toy stores don't use distributors - instead, they'll order directly or from sales reps

- GAMA is a good way to meet up with distributors

- Reps might also be an option if you can interest them

- Market is multi-level

- Distributor

- Retailer

- Customer

- You should talk to each of these folks to gauge marketability

- Alliance would be a good source to talk to; building a relationship with them (and listening to their feedback) is very useful, since they're so big

- Majority of new game companies fail - 90% of them fail

- Breaking even is success

- Art costs - can be a couple thousand dollars even for simple games

- Might be worth it, but only if you're definitely self-publishing, and even then probably not

- Art schools, commissions are ways around the costs

- Why do game companies fail?

- It takes lots of work, and you may not be able or willing to put in that effort

- Unreasonable expectations

- Very limited return, and gets frustrating on all the work

- Lack of preparation - getting the design, production, or marketing wrong

- Patents are silly

- Game designs are very difficult to steal, and also very difficult to protect

- Stealing isn't worth it

- Ideas are duplicated

This was also good stuff - not quite as new to me or as insider-y as the Chinese manufacturing talk, but good to hear lots of my suspicions and intuitions confirmed.

Friday, June 4, 2010

Manufacturing in China - Dan Tribbles GTS09 talk

At the recommendation of reader Hulken, I'm listening to this show: GTS 09: Getting the most out of your Chinese manufacturer. This is great stuff.

The speaker is Dan Tibbles, CEO, designer, and producer from Bucephalus Games (BGG profile here).

Some interesting points (I'm taking notes as I go):

Initial contact

Update: These are available in non-iTunes format at PulpGamer.com - the China one is here - thanks to commenter Eric Hanuise for the link.

- He suggests requesting domestic game publishers for recommendations for factories

- There are hundreds of thousands of printing companies in China, but very few of them are able to make quality cards and boards

- Try for three different factories, and send each of them a sample game as close to production quality as you can

- Boardgames are a somewhat alien concept for the Chinese; they need help understanding what you want

- You need to be extremely specific about components - e.g. paper weights, coatings, etc. - this is where examples work better

- You should ask for a quote and a sample; they'll make free samples, but you need to pay for shipping

- Quality is extremely variable, and prices reflect this quality for the most part

- Get the pricing broken down by component, not for the whole thing

- Cross-cultural communication is very difficult; use examples (actual samples) instead of words

- UPS to China and back is $100-$200

- They're willing to go through several iterations back and forth

- New publishing companies - pay half of production run up front, plus set-up charges (tools, molds, plates, etc.)

- Card sheet setup charge = $300

- Game board setup charge = $400

- Plastic figure from mold = $3000-4000 minimum, can get very large; each figure is very cheap

- Metal figure mold = $800, but each figure is expensive

- Part-time, hobbyist publisher (like me) should aim for 2000-2500 games starting print run

- Big push, with marketing money, no more than 5000 copies

- Minimum would be 1000-2000 for Chinese printing

- The reason there's the big drop in price is that there's a bunch of waste - maybe 1,000 copies are printed and thrown away before the colors are right, the press is ready, etc. So, your costs reflect these extra wasted materials.

- Blind rules testing is important - get readers to check your rules out for clarity

- Files need to be in great shape before sending - these turn into print proofs, which can cost several hundred dollars; they get sent back and forth

- Colors are never going to be perfect - often close, but not perfect; three iterations of back and forth sending is about the limit for this being useful

- It takes 30-60 days to get everything right before production, and then there's production and shipping; four months is a reasonable smooth timeline with few problems.

- Files should be totally flattened (i.e., no separate layers); no fonts, no stuff that can be moved or edited; everything should be graphical rather than text or font-based

- Make all changes yourself; don't request that they make edits, since the words and grammar can be messed up

- Factories should have Illustrator, Quark, Photoshop; file format isn't super-important, but make sure it's flattened.

- Payment - send purchase order over to factory; shouldn't be more than 50% up front; 30% up front is also good. They'll expect the balance when the product ships - not when it arrives.

- You will send payment by wire transfer to their bank account

- With lots of pieces, some may be outsourced; more complex means more time in production

- Tip - you should request to see and approve the first few units of the production run - "top of production" samples - as a final proof

- As a small, new customer, you will have very low status; the factory will prioritize other people and other projects; this can take lots of time

- Don't be in a hurry; be willing to use slow shipping for proofs and

- Quality control for whole run is hard to do; you can do it in person, or you can hire somebody to do it, but it's difficult for small new companies

- Big wood pieces (e.g. gameboards, large parts) have the most variation, so they're the biggest concern - not little pieces, which are generally OK.

- He's worked with maybe 60 companies over there, but would only work with about 10 of them again.

- Factories don't arrange for shipping - it's up to you

- Air shipping - very expensive; maybe $6 per game; 4-7 days

- Ocean shipping - two options

- LCL - Limited container load - you get a little piece of a container, shared with others

- FCL - Full container load - you rent the whole container - but it doesn't matter how full it is - not charged by weight, just volume

- 20' container is 1/2 as much by LCL

- 40' container is 1/2 as much per game as 20' (does this make sense?)

- Might still be cheaper to get a 20' container than go LCL

- Damage rate might be 2%, but more if fragile, and more if they are susceptible to water damage - e.g. wood parts expanding, warping from humidity

- Every single game should be shrink-wrapped individually

- Open at least 5% of the run to see if there are problems; more if there look to be issues

- It can be worth shopping around to get a good rate on a container - the rates will be extremely variable; individual discounts can be big, and you can play the companies off of each other

- Examples:

- 20' container from China to the West Coast of US - $1800-2200

- 40' container from China - $3000

- Depends on fuel

- Extra charges - taxes, paperwork, government fees, fuel surcharge

- They can probably give you an estimate for the whole shipment except for import duties

- Shipping company can handle transport within the US too - can go on trains or trucks

- Shipping - China to the U.S. West Coast - 2-3 weeks, plus another week of factory to ship, plus time to go through customs in U.S.

- Customs can be nearly nothing, not even inspected, or it can be a detailed search, but you have no real control. If you do get inspected, it will cost you a few hundred dollars a day for storage, and it may take several days.

- Good paperwork will help - everything from the factory should have a value included; shipping company can help with this.

- Wood products can include formaldehyde, so wood components (especially plywood) can give you problems

- Customs bond - required to go through customs - this is either $500/year, or $200-300 per container shipped

- Timing is tricky - you can't pay until it clears customs, but you don't know when that will be, and you pay for every day of storage, so you want to pay as fast as possible so you don't pay for needless storage

- Tip #1: Low prices mean low quality; there aren't many companies that rip people off now, but quality will vary

- Tip #2: Proofs won't look like production run, since they're done on different machines. Things will be wrong; you need to point these out, and check again in the top-of-production sample. This can be pretty major stuff; e.g. game board, cards not printed correctly or cut correctly as they will be on final production run.

- Tip #3: English won't always be good - keep asking until you understand; you won't offend them as long as you're talking business.

- Tip #4: They are 9-10 hours from us; their e-mails will come in the evening U.S. time.

- Tip #5: You should be able to save 30-70% even with shipping; more on stuff that requires lots of manpower

Wow, that was one of the most useful things I've listened to. Very good stuff, lots of questions answered. I'd recommend it to anybody.

Update: These are available in non-iTunes format at PulpGamer.com - the China one is here - thanks to commenter Eric Hanuise for the link.

Tuesday, June 1, 2010

Manufacturing quotes

I sent around for a few more manufacturing quotes over the last couple of days. One source in China says they can do the games for $1.32 each, FOB China. What I've learned FOB means is that they get it onto a ship somewhere in China, and I'm responsible for the transport, tracking, customs, insurance, and additional shipping within the U.S. once the product reaches here.

My problem is that I don't have much of a way to know what that's going to cost. Also, the rest of the quote is very limited in terms of details, so I don't even know what to ask about in terms of size, weight, number of cartons, etc. I've asked for more information, and I've done some research, but it's pretty frustrating - the production price sounds very good there, but without the shipping and importation costs, it's hard to know how good a deal it would end up being.

Not to mention the difficulties involved in working with people and sending money halfway around the world, where our laws don't apply and recourse is nearly impossible. But if I can save myself many thousands of dollars, I'd better look into it.

I'm also looking at a few more domestic printing options, so hopefully I can get a comparison there. Interesting stuff, but I'm in the dark on a lot of this, working to enlighten myself.

My problem is that I don't have much of a way to know what that's going to cost. Also, the rest of the quote is very limited in terms of details, so I don't even know what to ask about in terms of size, weight, number of cartons, etc. I've asked for more information, and I've done some research, but it's pretty frustrating - the production price sounds very good there, but without the shipping and importation costs, it's hard to know how good a deal it would end up being.

Not to mention the difficulties involved in working with people and sending money halfway around the world, where our laws don't apply and recourse is nearly impossible. But if I can save myself many thousands of dollars, I'd better look into it.

I'm also looking at a few more domestic printing options, so hopefully I can get a comparison there. Interesting stuff, but I'm in the dark on a lot of this, working to enlighten myself.

Monday, May 17, 2010

The importance of theme, or how to choose an audience

Following up on yet another topic from my Paper Money discussion, it's interesting that the uber-gamers I've played with have usually been more excited about my game Cult than with what I think is my more mainstream game, Diggity. Whenever I bring both to my weekly Guilford game-playing group, among people who've tried neither, Cult usually gets people the most excited. That's always been interesting to me - I think of Diggity as an easier-to-learn, quicker-to-play, far-less-luck-intensive game, but among the gamer set, Cult is more appealing, at least for a first try. I guess the premise of running your own cult and stealing followers from others is maybe a more gamer-y thing. I've certainly built more humor into the cards, with silly stuff you can base your cult around, and cards that are called funny things and have quirky powers.

I enjoy both games a lot. I think Diggity is the "better" one - more replay value, more strategic depth, less luck. But the theme seems to be less of a draw to people who are dedicated gamers. So, I'm left with several questions:

I enjoy both games a lot. I think Diggity is the "better" one - more replay value, more strategic depth, less luck. But the theme seems to be less of a draw to people who are dedicated gamers. So, I'm left with several questions:

- Would the theme of Cult also be more appealing to a non-gamer audience? I'm not sure. People are sometimes squishy about religious topics. The mechanics, with lots of cards with lots of words and a more complex system of turns, are harder to learn.

- Would Diggity be more appealing if I re-themed it to something quirkier, or more geek-friendly? Maybe, but I don't think so. The mining theme actually fits the mechanics pretty well, which is why I picked it; I suppose I could come up with something else that tried to connect the card-linking and part-building aspects, but I don't know what that would be.

- Which is the better one to market? This is a real toughie. If Diggity appeals more to non-gamers, then that's a bigger potential audience. But if Cult appeals more to gamers, I need to keep in mind they're proven game buyers. Then it becomes a numbers game - a bigger audience, or a more responsive one - and I don't really know enough to answer that. Maybe if I get to the point where I have both games in release, I'll be able to; at this point, I can't.

Labels:

Design,

Publishing

Sunday, May 16, 2010

NDA? No way.

On the Paper Money broadcast, the topic of NDAs (non-disclosure agreements) came up. I think Ben brought it up in jest, and I responded to the topic. The behavior in question here is the reluctance on the part of many newbie game designers to share what they've made with others. In the most egregious cases, this manifests as something like expecting a game publisher to sign an NDA before even looking at a game design for potential publication. In less acute forms, it's refusing to post an idea, or to offer your game for playtesting, for fear of idea theft.

Are there individual cases where game designs have actually been stolen, submitted by the thieves, and published? Yeah, there are probably a few, although most of them are of the "I knew this guy who knew a guy..." unverifiable variety, and the others are often cases where somebody saw an idea, modified it, and came up with a better way to implement it. In my life, I know a guy whose mother (the story goes) invented Monopoly, and the idea was copied by a guest (Mr. Darrow) and sold to Parker Brothers. But even that story doesn't line up with other versions of history. My own uncle was convinced that his idea for a train game had been stolen by a company he submitted it to, but without knowing the details it's hard to evaluate.

But even if you're swayed by this kind of story, going into full paranoia mode isn't warranted, I think. Here's why:

So, I'm going for the full disclosure strategy. I've had my game rules published on the web for six months now, so if anybody were to copy anything, it would be obvious where it came from. And because of this, and because of sharing the game with anybody who's willing to try it, I've had the benefit of feedback, commentary, and discussion. The world can be a nasty, backbiting place, but I haven't found the game design community to be so. I guess I'd rather take part in it and learn from it than hide behind the door with a shotgun.

UPDATE: Since writing this, I've run across this fine article by Shannon Applecline which addresses many of the same issues, with case studies.

Are there individual cases where game designs have actually been stolen, submitted by the thieves, and published? Yeah, there are probably a few, although most of them are of the "I knew this guy who knew a guy..." unverifiable variety, and the others are often cases where somebody saw an idea, modified it, and came up with a better way to implement it. In my life, I know a guy whose mother (the story goes) invented Monopoly, and the idea was copied by a guest (Mr. Darrow) and sold to Parker Brothers. But even that story doesn't line up with other versions of history. My own uncle was convinced that his idea for a train game had been stolen by a company he submitted it to, but without knowing the details it's hard to evaluate.

But even if you're swayed by this kind of story, going into full paranoia mode isn't warranted, I think. Here's why:

- Your game idea isn't that good. The odds that you have come up with a game even worth stealing are tiny. It probably sucks, at least in its current form. If you don't show it to anybody, it will continue to suck, alone, in the darkness.

- Even if your game is good, your game idea isn't unique. There are probably fifteen other people who've come up with a similar idea, so it can't really even be stolen from you. There aren't that many ways to get people to interact in a traditional game sense, so there aren't that many possible game designs.

- Even if your idea is unique, your mechanics can't be protected. There's no way to copyright or trademark a game mechanic or theme. I'm not a lawyer, but the rules are pretty simple to understand. You can copyright text, artwork, and some elements of graphic design (these are easy to protect; it's nearly automatic as soon as you create it). You can trademark words and artwork (these are significantly harder to protect). You can patent an actual physical invention or a method of doing something, but most boardgame patents are frivolous, over-broad, or end up being unpatentable.

- Even if your game is good, your idea unique, and your concept somehow protectable, the odds that you'll get published are minuscule. And forcing somebody to sign an NDA before even looking at the thing almost guarantees that you'll not even get looked at.

So, I'm going for the full disclosure strategy. I've had my game rules published on the web for six months now, so if anybody were to copy anything, it would be obvious where it came from. And because of this, and because of sharing the game with anybody who's willing to try it, I've had the benefit of feedback, commentary, and discussion. The world can be a nasty, backbiting place, but I haven't found the game design community to be so. I guess I'd rather take part in it and learn from it than hide behind the door with a shotgun.

UPDATE: Since writing this, I've run across this fine article by Shannon Applecline which addresses many of the same issues, with case studies.

Labels:

Design,

Publishing

Saturday, May 15, 2010

Getting printing quotes

In my interview(s) with the Paper Money guys, I mentioned (as I have on the blog here) that I've had some trouble getting quotes back from printers - slow responses, or no response, in many cases. My memory is already fuzzy, but I think this was in the first interview, which didn't get recorded, so I'll share it here. Ben responded with some interesting information - he estimated that only 10% of requests for quotes actually turn into printing orders (I would have guessed a much lower percentage, by the way), and that doing a quote can take 3-5 days of work, including waiting for estimates from different parts of the production run. So, that confirms my suspicions - some of the slow response or non-response probably comes from the fact that most of their efforts are wasted anyway.

Heck, I've gotten ten quotes from seven different companies, so I'm already nearing that 10% response level. No wonder they're not talking to me. Except that I'm the guy who will send one of them a big check, so you'd think they'd at least give me the time of day.

Heck, I've gotten ten quotes from seven different companies, so I'm already nearing that 10% response level. No wonder they're not talking to me. Except that I'm the guy who will send one of them a big check, so you'd think they'd at least give me the time of day.

Friday, May 14, 2010

Game printing costs

So, I mentioned earlier that Imagigrafx is no longer printing games. I had sought bids from them to produce my game, Diggity. The final product here would consist of about 100 cards, a rule sheet, and a box.

My first instinct was to treat these as confidential, for two reasons. One is, it's kind of unfair to Imagigrafx to publish their bids, because they're a competitive business, and it would let all their competitors know immediately what they're charging and how to undercut them. The second one is similar, but for my business; publishing this information might let potential customers of mine (or distributors, or whatever) know what my costs of production are like, and then use that knowledge to shape their pricing and purchasing decisions.

But I've moved on to my second instinct. My first reservation above, preserving trust with the printer, is not important now. The bids I've received from Imagigrafx are never going to be honored, so it's not hurting them to share the info with the public here. Just to be sure, I asked permission from the source of the quotes, Ben Clark, formerly the games contact at Imagigrafx, now co-host of Paper Money, and he graciously approved. As for my second reservation, keeping my production info private, there's still some concern there, I guess, but the point of this blog is primarily to be useful to my fellow game designers, and I think what I'm learning would be pretty helpful.

So, here's a summary (not the nitty-gritty) of the bids I got from Imagigrafx. They were an American printing company; I found their prices mostly competitive with other printers I consulted, and I was strongly considering going with them to avoid the hassle and uncertainty of working overseas. As for the information here, Ben had some caveats about using these quotes as representative of U.S. printing costs. Prior to exiting the business, Imagigrafx had increased some prices on shorter print runs, and that may have pushed them above other competing printers. This is especially true for the card printing costs; apparently, there was a mandate from higher up in the company to increase card printing prices.

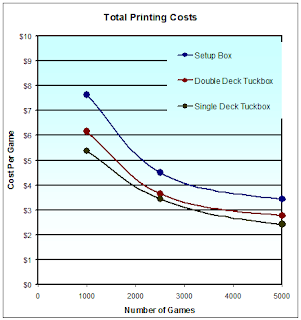

There are three columns here representing three different ways to produce the game. The first is the path I'd like to pursue - a larger two-piece box with a cardboard platform insert, with a cut-out hole where the deck of cards sits. The second and third columns are for one-piece tuckboxes. The second column would have the cards split into two stacks side by side. The third column is the cheapest, and has a single, thick, 100 card stack. For more discussion on these different box types, see here.

The top table shows the fixed setup costs (costs to make cutting dies and deliver proofs), marked in yellow, and then the per-game printing costs. The middle table shows the size of the actual check I'd be writing, or nearly so - there would be shipping costs too. The bottom table shows the final cost of goods - my cost per printed game. It's the first table with the setup costs worked into the per-game cost.

Here's that third table graphed up - you can see there's a huge price drop (about 40%) between 1000 and 2500 games, and another big drop (another 15% or so) between 2500 and 5000. Not so big a change between 5000 and 10000.

Remember that if you're relying on distributors, you're going to be getting only 35-40% of retail for your games, and you have a bunch of costs other than production costs. The wise sages of the industry recommend that your costs be 15%-25% of retail. So, a game you can produce for, say, $3.50 has to retail for $14-24 to fit the industry viability model, and a price at the upper end of that range would be hard for something like Diggity to bring in. I talked more on those economics in my earlier post here.

I hope this helps - the numbers are somewhat sobering, but you need to be informed to make good decisions.

UPDATE: To be clear, the prices above are for the whole game, including cards, rule sheet, box, and a cardboard insert in the case of the setup box.

My first instinct was to treat these as confidential, for two reasons. One is, it's kind of unfair to Imagigrafx to publish their bids, because they're a competitive business, and it would let all their competitors know immediately what they're charging and how to undercut them. The second one is similar, but for my business; publishing this information might let potential customers of mine (or distributors, or whatever) know what my costs of production are like, and then use that knowledge to shape their pricing and purchasing decisions.

But I've moved on to my second instinct. My first reservation above, preserving trust with the printer, is not important now. The bids I've received from Imagigrafx are never going to be honored, so it's not hurting them to share the info with the public here. Just to be sure, I asked permission from the source of the quotes, Ben Clark, formerly the games contact at Imagigrafx, now co-host of Paper Money, and he graciously approved. As for my second reservation, keeping my production info private, there's still some concern there, I guess, but the point of this blog is primarily to be useful to my fellow game designers, and I think what I'm learning would be pretty helpful.

So, here's a summary (not the nitty-gritty) of the bids I got from Imagigrafx. They were an American printing company; I found their prices mostly competitive with other printers I consulted, and I was strongly considering going with them to avoid the hassle and uncertainty of working overseas. As for the information here, Ben had some caveats about using these quotes as representative of U.S. printing costs. Prior to exiting the business, Imagigrafx had increased some prices on shorter print runs, and that may have pushed them above other competing printers. This is especially true for the card printing costs; apparently, there was a mandate from higher up in the company to increase card printing prices.

There are three columns here representing three different ways to produce the game. The first is the path I'd like to pursue - a larger two-piece box with a cardboard platform insert, with a cut-out hole where the deck of cards sits. The second and third columns are for one-piece tuckboxes. The second column would have the cards split into two stacks side by side. The third column is the cheapest, and has a single, thick, 100 card stack. For more discussion on these different box types, see here.

The top table shows the fixed setup costs (costs to make cutting dies and deliver proofs), marked in yellow, and then the per-game printing costs. The middle table shows the size of the actual check I'd be writing, or nearly so - there would be shipping costs too. The bottom table shows the final cost of goods - my cost per printed game. It's the first table with the setup costs worked into the per-game cost.

Here's that third table graphed up - you can see there's a huge price drop (about 40%) between 1000 and 2500 games, and another big drop (another 15% or so) between 2500 and 5000. Not so big a change between 5000 and 10000.

Remember that if you're relying on distributors, you're going to be getting only 35-40% of retail for your games, and you have a bunch of costs other than production costs. The wise sages of the industry recommend that your costs be 15%-25% of retail. So, a game you can produce for, say, $3.50 has to retail for $14-24 to fit the industry viability model, and a price at the upper end of that range would be hard for something like Diggity to bring in. I talked more on those economics in my earlier post here.

I hope this helps - the numbers are somewhat sobering, but you need to be informed to make good decisions.

UPDATE: To be clear, the prices above are for the whole game, including cards, rule sheet, box, and a cardboard insert in the case of the setup box.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)